Advent Of Code - Day 1

Since 2015, Advent Of Code has been a part of my life. I’ve done various posts on it already, but this year will be different. I’m going to blog every day every solution, why and how I’ve gotten to that solution.

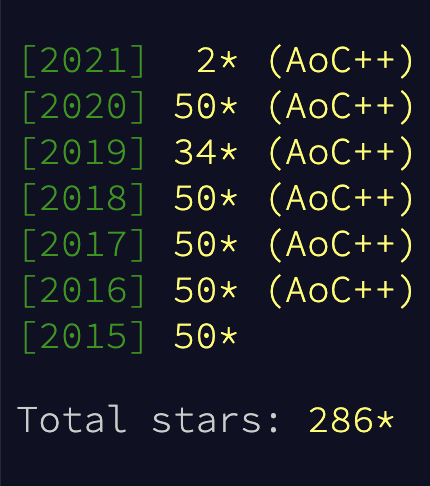

This isn’t going to be ever December, because I’m usually unable to solve a problem on a single day in the later days from day 10 or so. It takes more time then I have. But I will solve all of them. At the time of this writing, I have completed almost all puzzles except for year 2019 which I didn’t much enjoy to be honest.

A bit of history before we begin

I first heard of Advent Of Code when I joined Cheppers back in 2015. It was a great journey, and I loved every moment if it, but eventually I moved on. Advent of code, however, stayed with me over these past years. As someone without a formal CS education, I’m using these puzzles to catch up things I might have missed out. Everything I know I learned either by my self, or from books or videos or on the job. I begun coding at an early year and it stuck with me.

I really struggled with some of these problems, and I haven’t been able to completely solve a single year so far without seeking help. Every year, I’m getting closer and closer to solving all of the days, but it hasn’t happened yet.

It was amazing in identifying my weak areas. Things like, geometry problems ( I have forgotten everything from school ) ( asteroids had to be shot down going in a circle on a 2d matrix ), permutation problems, graph traversal, BFS, DFS, backtracking… As someone who never really had to deal with these things, I really lacked the know how.

As the years went by, and I solved all of the puzzles this way or that, and looked at what other people were cooking up, I begun to see that I started to improve in some of these areas.

I know why I didn’t improve in the areas I would have liked to improve in. And that is, lack of reflection. What do I mean by that? I solved the problem, read someone’s solution, then went on with my life. The way to get better at something is through reflection and recall though. And I didn’t do either.

So this year, I’m going to reflect and recall all my solutions, and even though I might need help in the later days, I will never use anyone else’s code. I will always write my own. And then, reflect upon it, by writing a post and talking about why this solution works or how I’ve gotten to it.

I also decided to finally create an SDK with all the common functions I’m using.

Day 1

History out of the way, let’s break down day 1.

Part 1

As usual, the first couple days are warmup. Easy problems to get your brain started into the right move and set up the story. Which is my favorite thing in all of this! Reasons why AOC is so awesome, is that it has an actual story! It isn’t just leetcode, or spoj or codewars or whatever. There is an actual story and it’s hilarious and a good read. And the problems aren’t just, solve x, solve y. They usually are diverse in some sense.

Part 1 this year, sets us up on a wild ride under the sea. The keys dropped into the water and we hopped into a submarine to go after it.

Let’s examine the problem.

How do I read AOC problems? First, I’m reading the story. I’m not in a hurry. I don’t want to be on the leader board. That’s not gonna happen. Then, I’m examining the problems and write down all the constraints ( aka, rules ).

For Part 1:

- we have a set of numbers

- they are all positive integers ranging from 100 - 9999 ( it’s important to identify your working sample as your solution depends on it )

- which means we can assume that there won’t be any negative numbers, floats, complex numbers, etc. ( narrows down the solution sample size )

The first order of business is to figure out how quickly the depth increases, just so you know what you’re dealing with - you never know if the keys will get carried into deeper water by an ocean current or a fish or something.

- we need depth increases ( what does this mean? ) ( we read on to find out more )

To do this, count the number of times a depth measurement increases from the previous measurement.

It’s important to see what things are in bold. They provide rules, hints and further clues. It’s also important to read and re-read every sentence PROPERLY AND THOROUGHLY. Because sometimes they are confusing on purpose. From the above we gather the following rule:

- count the number of times a number in the list increases compared to the previous one (numbers[n+1] > numbers[n])

And here is a tiny tidbit that I’m sure folks will glance over and yet it’s very important! In parentheses!

(There is no measurement before the first measurement.)

Meaning, you don’t compare the first one. This could cause a off by one error in part 2. It’s important to pay attention.

Then we have the example, and we are off.

Code

Essentially we just loop through all numbers that we gathered, and if there is a bigger number as the current one we increase a counter.

counter := 0

for i := 0; i < len(n)-1; i++ {

if n[i+1] > n[i] {

counter++

}

}

fmt.Println("Number of increases:", counter)

That’s it. We test it on the test which should yield the right number then we run it on our input, which also should yield the right number. This runs at a reasonable pace, so I think we are fine on optimization.

Onwards to…

Part 2

As usually, with part 2, things get a bit more complex here. We now need to solve a sliding window of threes. This a bit confusing to read at first, but essentially, we just need to sum up groups and compare the sums. We have to still do that same thing as before, but now, we track a previous sum and we need to check the next 2 numbers in the list not just the current, and current + 1.

The term sliding-window can be a bit confusing here. It just means that we will compare a slice of the numbers. The A B C notation looks also weird

to me. This one is a bit better:

Consider a list like this 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. We compare [1+2+3], [2+3+4], [3+4+5], [4+5+6].

So the sliding window is basically a set of three numbers counted from your current number. Instead of numbers[n] and numbers[n+1] we will look at

numbers[n] + numbers[n+1] + numbers[n+2].

Following that the code changes a tiny bit:

counter := 0

prevsum := math.MaxInt

for i := 0; i < len(n)-1; i++ {

if n[i] + n[i+1] + n[i+2] > prevsum {

counter++

}

}

fmt.Println("Number of increases:", counter)

Why did I add the math.MaxInt? Because we don’t count the first one, as pointed out by the previous sentence in parentheses!

This should give us the right value and both stars.

Closing words

So this is it for day 1. This one was an easy day. It prepared you to read the problem description. Understand it, and prase out the rules of engagement.

The repository for all my solutions for AOC 2021 can be found here.

Thanks for reading,

Gergely.