Intro

Welcome. This is a longer post about how to deploy a Go backend with a React frontend on Kubernetes as separate entities. Instead of the usual compiled together single binary Go application, we are going to separate the two. Why? Because usually a React frontend is just a “static” SPA app with very little requirements in terms of resources, while the Go backend does most of the leg work, requiring a lot more resources.

Part two of this will contain scaling, utilization configuration, health probes, readiness probes, and how to make sure our application can run multiple instances without stepping on each other’s toes.

Note: This isn’t going to be a Kubernetes guide. Some knowledge is assumed.

Summary

This post details a complex setup of an infrastructure with a second part coming on scaling and how to make your application scalable in the first place by doing idempotent transactions or dealing with locking and several instances of the same application not stepping on each other’s foot.

This, part one, details how to deploy traditional REST + Frontend based application in Go + React, but not bundled together as a single binary, instead having the backend separate from the frontend. They key in doing so is explained at the Ingress section when talking about routing specific URIs to the backend and frontend services.

If you are familiar with Kubernetes and infrastructure setup, feel free to skip ahead to that section. Otherwise, enjoy the drawings or the writing or both.

Technology

The SPA app will be handled by Serve while the Go backend will use Echo. The database will be Postgres.

We are going to apply some best practices using Network Policies to cordon off traffic that we don’t want to go outside.

We will set up HTTPS using cert-manager and let’s encrypt. We’ll be using nginx as ingress provider.

Code

All, or most of the code, including the application can be found here:

Staple. The application is a simple reading list manager with user handling, email sending and lots of database access.

Let’s get to it then!

Kubernetes Provider

Let’s start with the obvious one. Where do you would like to create your Kubernetes cluster?

There are four major providers now-a-days. AWS EKS, GCP GKE, Azure AKS and DigitalOcean DKE. Personally, I prefer DO because, it’s a lot cheaper than the others. The downside is that DO only provides ReadWriteOnce persistent volumes. This gets to be a problem when we are trying to update and the new Pod can’t mount the volume because it’s already taken by the existing one. This can be solved by a good ol NFS instance. But that’s another story.

AWS’ was late to the party and their solution is quite fragile and the API is terrible. GCP is best in terms of technicalities, api, handling, and updates. Azure is surprisingly good, however, the documentation is most of the times out of date or even plain incorrect at some places.

Setup Basics

To setup your Kubernetes instance, follow DigitalOcean’s Kubernetes Getting Started guide. It’s really simple. When you have access to the cluster via kubectl I highly recommend using this tool: k9s.

It’s a flexible and quite handy tool for quick observations, logs, shells to pods, edits and generally following what’s happening to your cluster.

Now that we are all set with our own little cluster, it’s time to have some people move in. First, we are going to install cert-manager.

Note: I’m not going to use Helm because I think it’s unnecessary in this setting. We aren’t going to install these things in a highly configurable way and updating with helm is a pain in the butt. For example, for cert-manager the update with helm takes several steps, whilst updating with a plain yaml file is just applying the next version of the yaml file.

I’m not going to explain how to install cert-manager or nginx. I’ll link to their respective guides because frankly, they are simple to follow and work out of the box.

To install nginx, simply apply the yaml file located here: DigitalOcean Nginx.

To install cert-manager follow this guide: cert-manager. Follow the regular manifest install part, then ignore the Helm part and proceed with verification and then install your issuer. I used a simple ACME/http01 issuer from here: acme/http01

Note: That acme configuration contains the staging url. This is to test that things are working. Once you are

sure that everything is wired up correctly, switch that url to this one:

https://acme-v02.api.letsencrypt.org/directory -> prod url. For example:

apiVersion: cert-manager.io/v1alpha2

kind: ClusterIssuer

metadata:

name: letsencrypt-prod

spec:

acme:

# The ACME server URL

server: https://acme-v02.api.letsencrypt.org/directory

# Email address used for ACME registration

email: your@email.com

# Name of a secret used to store the ACME account private key

privateKeySecretRef:

name: letsencrypt-prod

# Enable the HTTP-01 challenge provider

solvers:

- http01:

ingress:

class: nginx

Note: I’m using a ClusterIssuer because I have multiple domains and multiple namespaces.

That’s it. Cert-manager and nginx should be up and running. Later on, we will create our own ingress rules.

Domain

Next, you’ll need a domain to bind too. There are a gazillion domain providers out there like no-ip, GoDaddy, HostGator, Shopify and so on. Choose one which is available to you or has the best prices.

There are some good guides on how to choose a domain and where to create it. For example: 5 things to watch out for when buying a domain.

The application

Alright, let’s put together the application.

Structure

Every piece of our infrastructure will be laid out in yaml files. I believe in infrastructure as code. If you run a command you will most likely forget about it, unless it’s logged and / or is replayable.

This is the structure I’m using:

.

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── certificate_request

│ └── certificate_request.yml

├── configmaps

│ └── staple_initdb_script.yaml

├── database

│ ├── staple_db_deployment.yaml

│ ├── staple_db_network_policy.yaml

│ ├── staple_db_pvc.yaml

│ └── staple_db_service.yaml

├── namespace

│ └── staple_namespace.yaml

├── primer.sql

├── rbac

├── secrets

│ ├── staple_db_password.yaml

│ └── staple_mg_creds.yaml

├── staple-backend

│ ├── staple_deployment.yaml

│ └── staple_service.yaml

└── staple-frontend

├── staple_deployment.yaml

└── staple_service.yaml

One other possible combination is, if you have multiple applications:

.

├── README.md

├── applications

│ ├── confluence

│ │ ├── db

│ │ │ ├── db_deployment.yaml

│ │ │ └── db_service.yaml

│ │ ├── deployment

│ │ │ └── deployment.yaml

│ │ ├── pvc

│ │ │ └── confluence_app_pvc.yaml

│ │ └── service

│ │ └── service.yaml

│ ├── gitea

│ │ ├── config

│ │ │ ├── app.ini

│ │ │ └── gitea_config_map.yaml

│ │ ├── db

│ │ │ ├── gitea_db_deployment.yaml

│ │ │ ├── gitea_db_network_policy.yaml

│ │ │ ├── gitea_db_pvc.yaml

│ │ │ └── gitea_db_service.yaml

│ │ ├── deployment

│ │ │ └── gitea_deployment.yaml

│ │ ├── pvc

│ │ │ └── gitea_app_pvc.yaml

│ │ └── service

│ │ └── gitea_service.yaml

├── cronjobs

│ ├── cronjob1

│ │ ├── Dockerfile

│ │ ├── README.md

│ │ ├── go.mod

│ │ ├── go.sum

│ │ ├── cron.yaml

│ │ └── main.go

├── ingress

│ ├── example1

│ │ ├── example1_ingress_resource.yaml

│ │ └── gitea_ssh_configmap.yaml

│ ├── example2

│ │ └── example2_ingress_resource.yaml

│ ├── lets-encrypt-issuer.yaml

│ └── nginx

│ ├── nginx-ingress-controller-deployment.yaml

│ └── nginx-ingress-controller-service.yaml

└── namespaces

├── example1_namespace.yaml

├── example2_namespace.yaml

Namespace

Before we begin, we’ll create a namespace for our application to properly partition all our entities.

To create a namespace we’ll use this yaml example_namespace.yaml:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Namespace

metadata:

name: example

Apply this with kubectl -f apply example_namespace.yaml.

The Database

Deploying a Postgres database on Kubernetes is actually really easy. You need five things to have a basic, but relatively secure installation.

Secret

The secret contains our password and our database user. In postgres, if you define a user using POSTGRES_USER

postgres will create the user and a database with the user’s name. This could come from Vault too, but

the Kubernetes secret is usually enough since it should be a closed environment anyways. But for important information

I would definitely use an admission policy and some vault secret goodness. (Maybe another post?)

Our secret looks like this: database_secret.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: staple-db-password

namespace: staple

data:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: cGFzc3dvcmQxMjM=

# This creates a user and a db with the same name.

POSTGRES_USER: c3RhcGxl

To generate the base64 code for a password and a user, use:

echo -n "password123" | base64

echo -n "username" | base64

…and paste the result in the respective fields. Once done, apply with kubectl -f apply database_secret.yaml.

Deployment

The deployment which configures our database. Looks something like this (database_deployment.yaml):

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: staple-db

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: staple-db

template:

metadata:

name: staple-db

labels:

app: staple-db

spec:

containers:

- name: postgres

image: postgres:11

env:

- name: POSTGRES_USER

value: staple

- name: POSTGRES_PASSWORD

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: staple-db-password

key: POSTGRES_PASSWORD

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /var/lib/postgresql/data

subPath: data # important so it gets mounted correctly

name: staple-db-data

- mountPath: /docker-entrypoint-initdb.d/staple_initdb.sql

subPath: staple_initdb.sql

name: bootstrap-script

volumes:

- name: staple-db-data

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: do-storage-staple-db

- name: bootstrap-script

configMap:

name: staple-initdb-script

Note the two volume mounts.

The first one makes sure that our data isn’t lost when the database pod itself restarts. It creates a mount

to a persistent volume which is defined a few lines below by persistentVolumeClaim. subPath is important

in this case otherwise you’ll end up with a lost&found folder.

The second mount is a postgres specific initialization file. Postgres will run that sql file when it starts up. I’m using it to create my application’s schema.

create database staples;

create table users (email varchar(255), password text, confirm_code text, max_staples int);

create table staples (name varchar(255), id serial, content text, created_at timestamp, archived bool, user_email varchar(255));

And it comes from a configmap which looks like this:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: staple-initdb-script

namespace: staple

labels:

app: staple

data:

staple_initdb.sql:

create table users (email varchar(255), password text, confirm_code text, max_staples int);

create table staples (name varchar(255), id serial, content text, created_at timestamp, archived bool, user_email varchar(255));

Network Policy

Network policies are important if you value your privacy. They restrict a PODs communication to a certain namespace OR even to between applications only. By default I like to deny all traffic and then slowly open the valve until everything works.

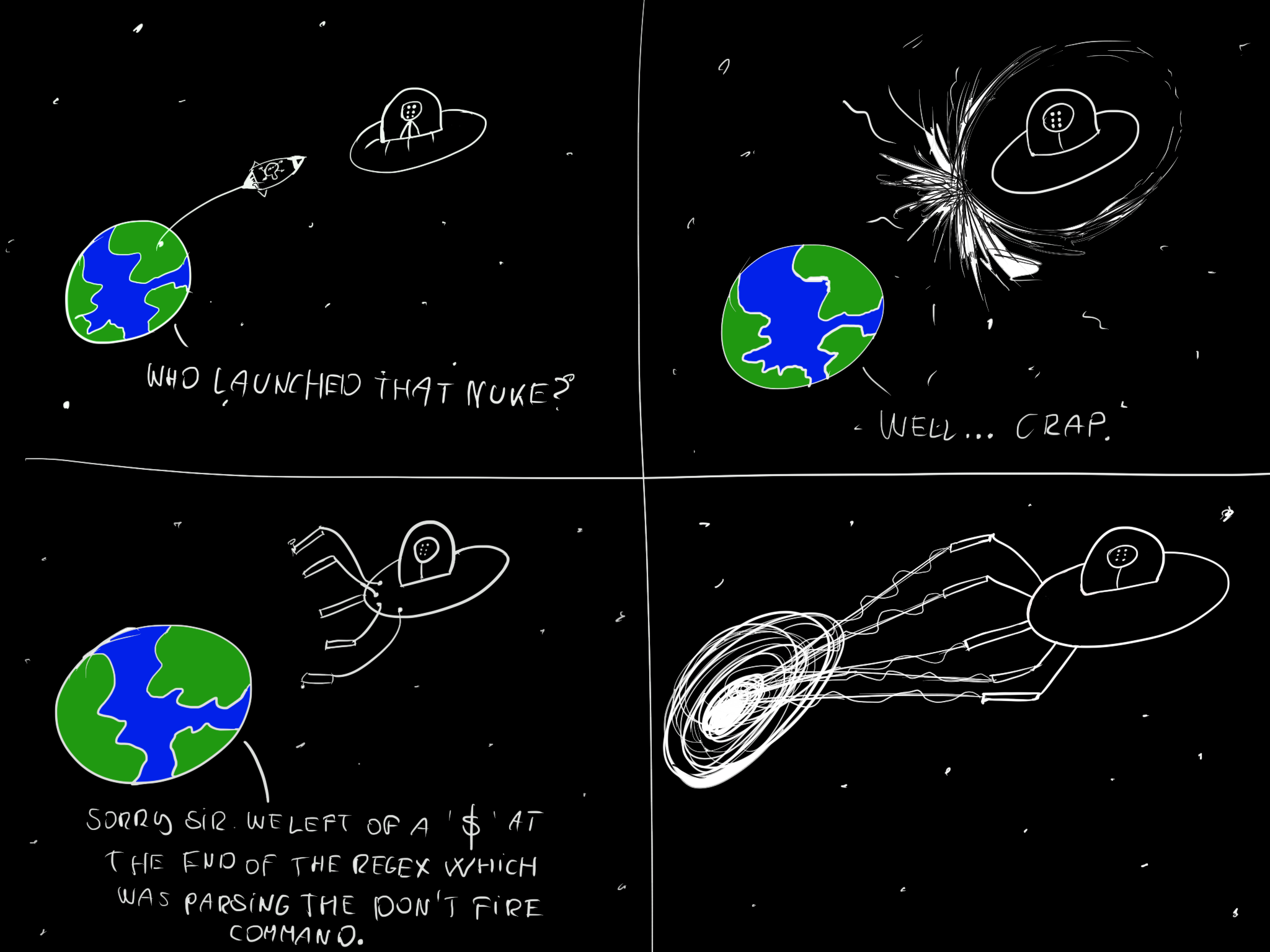

Kudos if you know who this is. (mind my terrible drawing capabilities)

Kudos if you know who this is. (mind my terrible drawing capabilities)

We’ll use a basic network policy which will restrict the DB to talk to anything BUT the backend. Nothing else will be able to talk to this Pod.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: staple-db-network-policy

namespace: staple

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: staple-db

policyTypes:

- Ingress

- Egress

ingress:

- from:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: staple

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 5432

egress:

- to:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: staple

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 5432

The important bit here is the podSelector part. The label will be the label used by the application deployment.

This will restrict the Pod’s incoming and outgoing traffic to that of the application Pod including denying internet

traffic.

PVC

The persistent volume claim definition is straight forward:

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: do-storage-staple-db

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

resources:

requests:

storage: 10Gi

storageClassName: do-block-storage

10 gigs should be enough anything.

Service

The service will expose the database deployment to our cluster.

Our service is fairly basic:

kind: Service

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: staple-db-service

spec:

ports:

- port: 5432

selector:

app: staple-db

clusterIP: None

That’s done with the database. Next up is the backend.

The backend

The backend itself is written in a way that it doesn’t require a persistent storage so we can skip that part. It only needs three pieces. A secret, a deployment definition and the service exposing the deployment.

Secret

First, we create a secret which contains Mailgun credentials.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: staple-mg-creds

namespace: staple

data:

MG_DOMAIN: cGFzc3dvcmQxMjM=

MG_API_KEY: cGFzc3dvcmQxMjM=

Database connection

The connection settings are handled through the same secret which is used to spin up the DB itself. We have to only mount that here too and we are good.

Deployment

Which brings us to the deployment. This is a bit more involved.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: staple-app

labels:

app: staple

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: staple

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: staple

app.kubernetes.io/name: staple

app.kubernetes.io/instance: staple

spec:

containers:

- name: staple

image: skarlso/staple:v0.1.0

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

resources:

requests:

memory: "500Mi"

cpu: "250m"

limits:

memory: "1000Mi"

cpu: "500m"

env:

- name: POD_NAMESPACE

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.namespace

- name: DB_PASSWORD

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: staple-db-password

key: POSTGRES_PASSWORD

- name: MG_DOMAIN

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: staple-mg-creds

key: MG_DOMAIN

- name: MG_API_KEY

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: staple-mg-creds

key: MG_API_KEY

args:

- --staple-db-hostname=staple-db-service.cronohub.svc.cluster.local:5432

- --staple-db-username=staple

- --staple-db-database=staple

- --staple-db-password=$(DB_PASSWORD)

- --mg-domain=$(MG_DOMAIN)

- --mg-api-key=$(MG_API_KEY)

ports:

- name: staple-port

containerPort: 9998

There are a few important points here and I won’t explain them all, like the resource restrictions, which you should be familiar with by now. I’m using a mix of 12factor app’s environment configuration and command line arguments for the application configuration. The app itself is not using os.Environ but the args.

The args point to the cluster local dns of the database, some db settings, and the mailgun credentials.

It also exposes the container port 9998 which is Echo’s default port.

Now all we need is the service.

Service

Without much fanfare:

kind: Service

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: staple-service

labels:

app: staple

app.kubernetes.io/name: staple

app.kubernetes.io/instance: staple

spec:

selector:

app: staple

app.kubernetes.io/name: staple

app.kubernetes.io/instance: staple

ports:

- name: service-port

port: 9998

targetPort: staple-port

And with this, the backend is done.

The frontend

The frontend, similarly to the backend, does not require a persistent volume. We can skip that one too.

In fact it only needs two things, a deployment and a service, and that’s all. It uses serve to host the static files. Honestly, that could also be a Go application serving the static content or anything that can serve static files.

Deployment

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: staple-frontend

labels:

app: staple-frontend

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: staple-frontend

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: staple-frontend

app.kubernetes.io/name: staple-frontend

app.kubernetes.io/instance: staple-frontend

spec:

containers:

- name: staple-frontend

image: skarlso/staple-frontend:v0.0.9

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

resources:

requests:

memory: "500Mi"

cpu: "250m"

limits:

memory: "1000Mi"

cpu: "500m"

env:

- name: POD_NAMESPACE

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.namespace

- name: REACT_APP_STAPLE_DEV_HOST

value: ""

ports:

- name: staple-front

containerPort: 5000

Service

And the service:

kind: Service

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: staple-front-service

labels:

app: staple-frontend

app.kubernetes.io/name: staple-frontend

app.kubernetes.io/instance: staple-frontend

spec:

selector:

app: staple-frontend

app.kubernetes.io/name: staple-frontend

app.kubernetes.io/instance: staple-frontend

ports:

- name: staple-front

port: 5000

targetPort: staple-front

And with that the backend and frontend are wired together and ready to receive traffic.

All pods should be up and running without problems at this point. If you have any trouble deploying things, please don’t hesitate to leave a question in the comments.

Ingress

Fantastic. Now, our application is running. We just need to expose it and route traffic to it.

The backend has the api route /rest/api/v1/. The frontend has the route syntax /login, /register

and a bunch of others. The key here is that all of them are under the same domain name but based on the URI

we need to direct one request to the backend the other to the frontend.

This is done via nginx’s routing logic using regex. In an nginx config this would be the location part.

It’s imperative that the order of the routing is from more specific towards more general Because we need to catch

the specific URIs first.

Ingress Resource

To do this, we will create something called an Ingress Resource. Note that this is Nginx’s ingress resource and not Kubernetes’. There is a difference.

I suggest reading up on that link about the ingress resource because it reads quite well and will explain how it works and fits into the Kubernetes environment.

Got it? Good. We’ll create one for staple.app domain:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

namespace: staple

name: staple-app-ingress

annotations:

kubernetes.io/ingress.class: "nginx"

cert-manager.io/cluster-issuer: "letsencrypt-prod"

cert-manager.io/acme-challenge-type: http01

nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/rewrite-target: /$1 # this is important

spec:

tls:

- hosts:

- staple.app

secretName: staple-app-tls

rules:

- host: staple.app

http:

paths:

- backend:

serviceName: staple-service

servicePort: ss-port # 9998

path: /(rest/api/1.*)

- host: staple.app

http:

paths:

- backend:

serviceName: staple-front-service

servicePort: sfs-port # 5000

path: /(.*)

Let’s take a look at what’s going on here. The first thing to catch the eye are the annotations. These are configuration settings for nginx, cert-manager and Kubernetes. We have the cluster issuer’s name. The challenge type, which we decided should be http01, and the most important part, the rewrite-target setting. This will use the first capture group as a base after the host.

With this rewrite rule in place, the paths values need to provide a capture group. The first in line will see

everything that goes to the urls like: staple.app/rest/api/1/token, staple.app/rest/api/1/staples,

staple.app/rest/api/1/user, etc. The first part of the url is the host staple.app, second part is /(rest/api/1/.*)

for which the result is that group number one ($1) will be rest/api/1/token. Nginx now sees that we

have a backend route for that and will send this URI along to the service. Our service picks it up

and will match that URI to the router configuration.

If there is a request like, staple.app/login, which is our frontend’s job to pick up, the first rule

will not catch it because the regex isn’t matching, so it falls through to the second one, which

is the frontend service that is using a “catch all” regex. Like ip tables, we go from

specific to more general.

Ending words

And that’s it. If everything works correctly, then the certificate service wired up the https certs and

we should be able ping the rest endpoint under https://staple.app/rest/api/1/token and log in to the app

in the browser using https://staple.app.

Stay tuned for the second part where we’ll scale the thing up!

Thanks for reading! Gergely.