Intro

Hi folks!

Today I would like to write about a metric that I read in a book called Clean Architecture from Robert Cecil Martin ( Uncle Bob ).

Abstract

The metrics I mean are Efferent and Afferent coupling in packages. So you, dear reader, don’t have to navigate away from this page, here are the descriptions pasted in:

Afferent couplings (Ca): The number of classes in other packages that depend upon classes within the package is an indicator of the package’s responsibility. Afferent couplings signal inward. (Affected by this package) (Fan-In).

Efferent couplings (Ce): The number of classes in other packages that the classes in this package depend upon is an indicator of the package’s dependence on externalities. Efferent couplings signal outward. (Effecting this package) (Fan-Out).

These metrics used together will indicate the stability / instability of each package in a project.

Metric Usage

What does it mean if the package is stable vs. unstable? Let’s take a closer look.

Unstable

If the instability metric comes out as 1 or close to 1, that means that the package is unstable. It means that there are only packages which this package is depending upon and nothing, or only 1 or 2, packages depend on it. This infers two things:

- The package is easy to change since there is nothing depending on the behavior explicitly

- The package is volatile since it depends on a lot of out side things

The first one is self-explanatory. The second one has ramifications. These ramifications are that there are a lot of packages that could cause bugs in this package. Ideally, a package with instability 1 or high, requires a large test coverage to ensure that no bugs seep in.

Stable

On the other spectrum lies the indicator for a stable package. If this metric is 0 or close to 0, the package is said to be stable. A stable package resists change because it has a lot of depending packages. The depending packages lock this package in place, meaning we can’t change the package easily. Ideally this is the package that would contain business logic for example, or code which does not change often.

Appliance in Go ecosystem

The book was using mostly Java or C/C++ for examples and dealt with classes describing these metrics. Especially the Abstractness of a package which calculates as ratio of abstract classes + interfaces vs concrete classes and implementations. This isn’t that easy to define in Go. Not impossible though and we could still get something close enough. Something like, count interfaces + structs vs implementations of said interfaces with function receivers and functions.

The easier of these is the coupling metrics. I think we can define them since Go also has import statements. Go doesn’t have classes, but it’s enough if we calculate the number of packages that said package depends upon and are depended upon by. Should be close enough.

Tool

If there is a project with a lot of packages and files, it would be quite difficult to calculate things using your hands… Hence, Effrit. This tool, at the writing of this post, only calculates the stability metric for now. If given a parameter like -p effrit it will only calculate the Fan-Out metrics considering project packages. If no project name is given, it will also calculate not project packages (for example cobra or aws sdk) as Efferent. Usage is really simple. Navigate to the root of the project and run effrit scan -p <projectname>.

Applying the tool

Let’s see with a real example on using the tool and what to do with the metrics it provides.

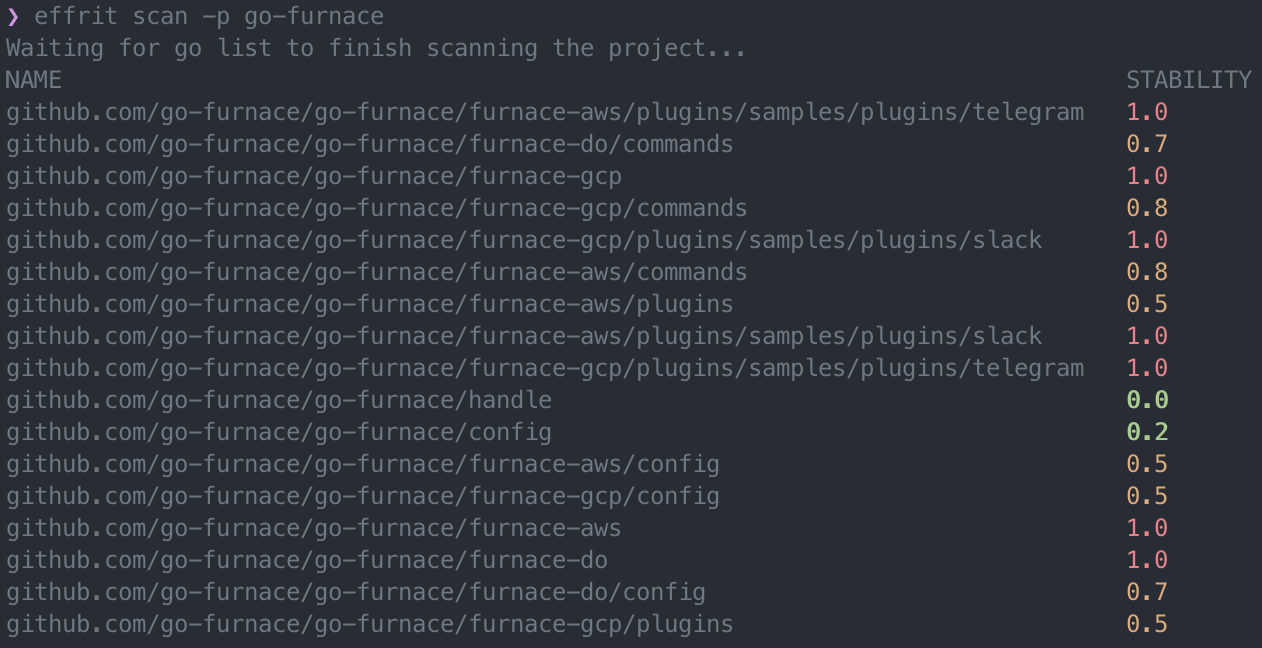

I have a project called Furnace. Running the tool on it I get the following stats:

.

.

What do these means?

It means, that hopefully, command packages have a high coverage and that config packages don’t require change that often. The coverage count for aws command package is:

coverage: 74.7% of statements

That is pretty good. I think it’s covered well enough for now.

On to the config package. This is the whole file:

package config

import (

"os/user"

"path/filepath"

"github.com/go-furnace/go-furnace/handle"

)

// Spinners is a collection os spinner types

var Spinners = []string{`←↖↑↗→↘↓↙`,

`▁▃▄▅▆▇█▇▆▅▄▃`,

`┤┘┴└├┌┬┐`,

`◰◳◲◱`,

`◴◷◶◵`,

`◐◓◑◒`,

`⣾⣽⣻⢿⡿⣟⣯⣷`,

`|/-\`}

// WAITFREQUENCY global wait frequency default.

var WAITFREQUENCY = 1

// STACKNAME is the default name for a stack.

var STACKNAME = "FurnaceStack"

// SPINNER is the index of which spinner to use. Defaults to 7.

var SPINNER = 7

// Path retrieves the main configuration path.

func Path() string {

// Get configuration path

usr, err := user.Current()

handle.Error(err)

return filepath.Join(usr.HomeDir, ".config", "go-furnace")

}

Not a lot of stuff in there. But it’s using the handle package. Hence the 0.2. Luckily, we also have some coverage to take care of that.

The handle is pretty stable. Let’s take a peak inside:

package handle

import "log"

// LogFatalf is used to define the fatal error handler function. In unit tests, this is used to

// mock out fatal errors so we can test for them.

var LogFatalf = log.Fatalf

// Error extracts the if err != nil check. If the given error is not nil it will call

// the defined fatal error handler function.

func Error(err error) {

if err != nil {

Fatal("Error occurred:", err)

}

}

// Fatal is a wrapper for LogFatalf function. It's used to throw a Fatal in case it needs to.

func Fatal(s string, err error) {

LogFatalf(s, err)

}

Basic logic to take care of errors in Furnace. Last time I changed this file was… a year ago. Yeah, I think it’s doing fine.

Conclusion

And that’s it. Hopefully this is an interesting metric to use to define what packages may need refactoring, or need to be repurposed because they are too rigid. If a packages is stable, aka. hard to change but must undergo changes frequently, it may be time to refactor and introduce a mediator or a liaison package. If a package is unstable and has a lot of bugs, we might want to refactor it and inverse it’s dependencies. This is called the Dependency Inversion Principle, DIP. Which is also described in the same book. However it’s not always bad if a package is unstable. Maybe it contains code which needs to change frequently. It’s a database schema code. Or an algorithm which requires constant tweaking. And that is fine. Just make sure it’s covered well enough.

The principles that these metrics are based on are: SAP and SDP. Stable Abstraction Principle and Stable Dependencies Principle. These are also described in the same book, Clean Architecture. A highly recommend it. Applying these principles could help maintain the project’s stability and it’s dependencies.

Thank you for reading, Gergely.