Intro

Alright folks. Settle in and get comfortable. This is going to be a long, but hopefully, fun ride.

I’m going to deploy a distributed application with Kubernetes. I attempted to create an application that I thought resembled a real world app. Obviously I had to cut some corners due to time and energy constraints.

My focus will be on Kubernetes and deployment.

Shall we delve right in?

The Application

TL;DR

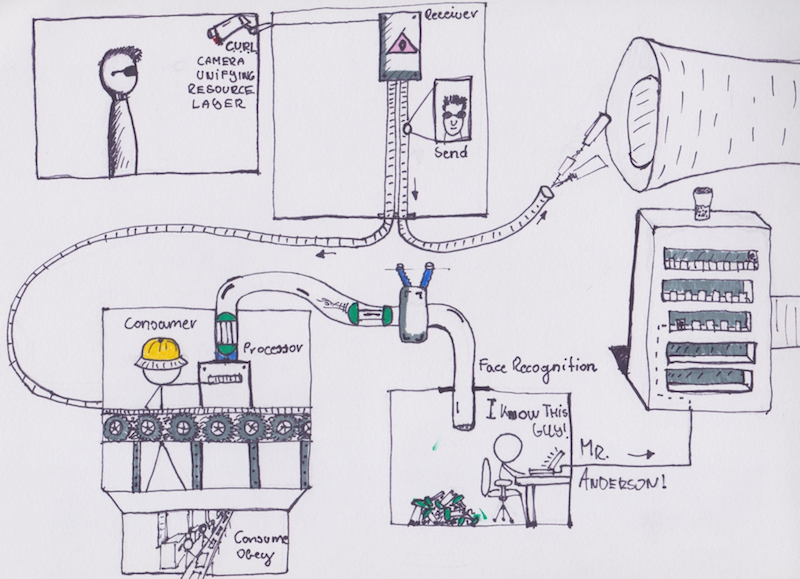

The application itself consists of six parts. The repository can be found here: Kube Cluster Sample.

It’s a face recognition service which identifies images of people, comparing them to known individuals. A simple frontend displays a table of these images whom they belong to. This happens by sending a request to a receiver. The request contains a path to an image. This image can sit on an NFS somewhere. The receiver stores this path in the DB (MySQL) and sends a processing request to a queue. The queue uses: NSQ. The request contains the ID of the saved image.

An Image Processing service is constantly monitoring the queue for jobs to do. The processing consists of the following steps: taking the ID; loading the image; and finally, sending the image to a face recognition backend written in Python via gRPC. If the identification is successful, the backend will return the name of the image corresponding to that person. The image_processor then updates the image’s record with the person’s ID and marks the image as “processed successfully”. If identification is unsuccessful, the image will be left as “pending”. If there was a failure during identification, the image will be flagged as “failed”.

Failed images can be retried with a cron job, for example:

So how does this all work? Let’s check it out .

Receiver

The receiver service is the starting point of the process. It’s an API which receives a request in the following format:

curl -d '{"path":"/unknown_images/unknown0001.jpg"}' http://127.0.0.1:8000/image/post

In this instance, the receiver stores the path using a shared database cluster. The entity will then receive an ID from the database service. This application is based on the model where unique identification for Entity Objects is provided by the persistence layer. Once the ID is procured, the receiver will send a message to NSQ. At this point in the process, the receiver’s job is done.

Image Processor

Here is where the excitement begins. When Image Processor first runs it creates two Go routines. These are…

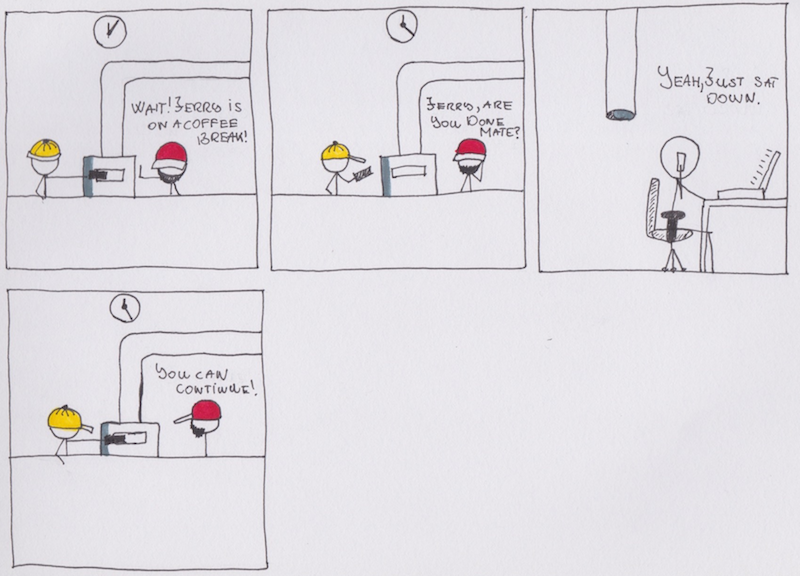

Consume

This is an NSQ consumer. It has three integral jobs. Firstly, it listens for messages on the queue. Secondly, when there is a message, it appends the received ID to a thread safe slice of IDs that the second routine processes. And lastly, it signals the second routine that there is work to be do. It does this through sync.Condition.

ProcessImages

This routine processes a slice of IDs until the slice is drained completely. Once the slice is drained, the routine suspends instead of sleep-waiting on a channel. The processing of a single ID can be seen in the following linear steps:

- Establish a gRPC connection to the Face Recognition service (explained under Face Recognition)

- Retrieve the image record from the database

- Setup two functions for the Circuit Breaker

- Function 1: The main function which runs the RPC method call

- Function 2: A health check for the Ping of the circuit breaker

- Call Function 1 which sends the path of the image to the face recognition service. This path should be accessible by the face recognition service. Preferably something shared like an NFS

- If this call fails, update the image record as FAILED PROCESSING

- If it succeeds, an image name should come back which corresponds to a person in the db. It runs a joined SQL query which gets the corresponding person’s ID

- Update the Image record in the database with PROCESSED status and the ID of the person that image was identified as

This service can be replicated. In other words, more than one can run at the same time.

Circuit Breaker

A system in which replicating resources requires little to no effort, there still can be cases where, for example, the network goes down, or there are communication problems of any kind between two services. I like to implement a little circuit breaker around the gRPC calls for fun.

This is how it works:

As you can see, once there are 5 unsuccessful calls to the service, the circuit breaker activates, not allowing any more calls to go through. After a configured amount of time, it will send a Ping call to the service to see if it’s back up. If that still errors out, it will increase the timeout. If not, it opens the circuit, allowing traffic to proceed.

Front-End

This is only a simple table view with Go’s own html/template used to render a list of images.

Face Recognition

Here is where the identification magic happens. I decided to make this a gRPC based service for the sole purpose of its flexibility. I started writing it in Go but decided that a Python implementation would be much sorter. In fact, excluding the gRPC code, the recognition part is approximately 7 lines of Python code. I’m using this fantastic library which contains all the C bindings to OpenCV. Face Recognition. Having an API contract here means that I can change the implementation anytime as long as it adheres to the contract.

Please note that there exist a great Go library OpenCV. I was about to use it but they had yet to write the C bindings for that part of OpenCV. It’s called GoCV. Check them out! They have some pretty amazing things, like real-time camera feed processing that only needs a couple of lines of code.

The python library is simple in nature. Have a set of images of people you know. I have a folder with a couple of images named, hannibal_1.jpg, hannibal_2.jpg, gergely_1.jpg, john_doe.jpg. In the database I have two tables named, person, person_images. They look like this:

+----+----------+

| id | name |

+----+----------+

| 1 | Gergely |

| 2 | John Doe |

| 3 | Hannibal |

+----+----------+

+----+----------------+-----------+

| id | image_name | person_id |

+----+----------------+-----------+

| 1 | hannibal_1.jpg | 3 |

| 2 | hannibal_2.jpg | 3 |

+----+----------------+-----------+

The face recognition library returns the name of the image from the known people which matches the person on the unknown image. After that, a simple joined query -like this- will return the person in question.

select person.name, person.id from person inner join person_images as pi on person.id = pi.person_id where image_name = 'hannibal_2.jpg';

The gRPC call returns the ID of the person which is then used to update the image’s ‘person` column.

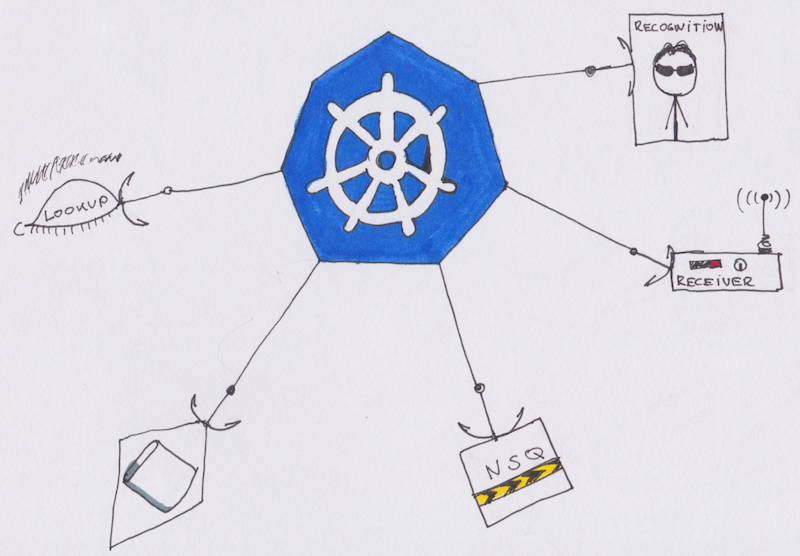

NSQ

NSQ is a nice little Go based queue. It can be scaled and has a minimal footprint on the system. It also has a lookup service that consumers use to receive messages, and a daemon that senders use when sending messages.

NSQ’s philosophy is that the daemon should run with the sender application. That way, the sender will send to the localhost only. But the daemon is connected to the lookup service, and that’s how they achieve a global queue.

This means that there are as many NSQ daemons deployed as there are senders. Because the daemon has a minuscule resource requirement, it won’t interfere with the requirements of the main application.

Configuration

In order to be as flexible as possible, as well as making use of Kubernetes’s ConfigSet, I’m using .env files in development to store configurations like the location of the database service, or NSQ’s lookup address. In production- and that means the Kubernetes’s environment- I’ll use environment properties.

Conclusion for the Application

And that’s all there is to the architecture of the application we are about to deploy. All of its components are changeable and coupled only through the database, a queue and gRPC. This is imperative when deploying a distributed application due to how updating mechanics work. I will cover that part in the Deployment section.

Deployment with Kubernetes

Basics

What is Kubernetes?

I’m going to cover some of the basics here. I won’t go too much into detail- that would require a whole book like this one: Kubernetes Up And Running. Also, if you’re daring enough, you can have a look through this documentation: Kubernetes Documentation.

Kubernetes is a containerized service and application manager. It scales easily, employs a swarm of containers, and most importantly, it’s highly configurable via yaml based template files. People often compare Kubernetes to Docker swarm, but Kubernetes does way more than that! For example: it’s container agnostic. You could use LXC with Kubernetes and it would work the same way as you using it with Docker. It provides a layer above managing a cluster of deployed services and applications. How? Let’s take a quick look at the building blocks of Kubernetes.

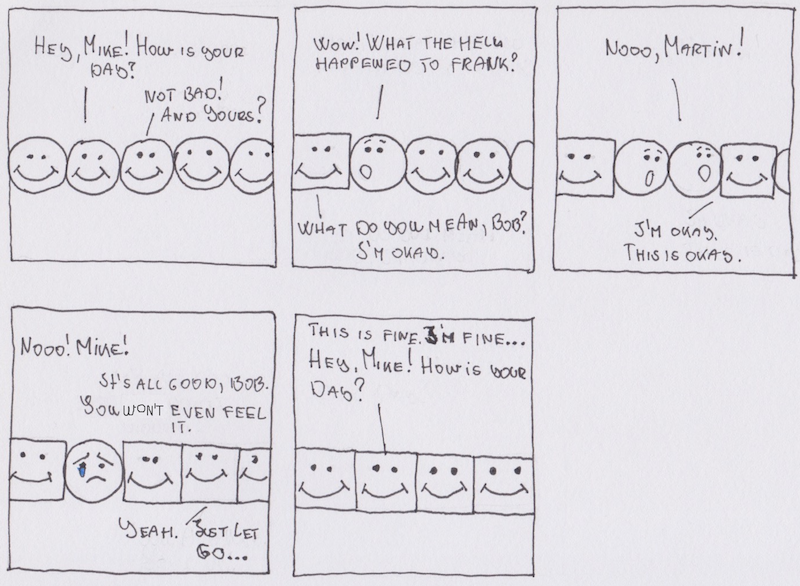

In Kubernetes, you’ll describe a desired state of the application and Kubernetes will do what it can to reach that state. States could be something such as deployed; paused; replicated twice; and so on and so forth.

One of the basics of Kubernetes is that it uses Labels and Annotations for all of its components. Services, Deployments, ReplicaSets, DaemonSets, everything is labelled. Consider the following scenario. In order to identify what pod belongs to what application, a label is used called app: myapp. Let’s assume you have two containers of this application deployed; if you would remove the label app from one of the containers, Kubernetes would only detect one and thus would launch a new instance of myapp.

Kubernetes Cluster

For Kuberenetes to work, a Kubernetes cluster needs to be present. Setting that up might be a tad painful, but luckily, help is on hand. Minikube sets up a cluster for us locally with one Node. And AWS has a beta service running in the form of a Kubernetes cluster in which the only thing you need to do is request nodes and define your deployments. The Kubernetes cluster components are documented here: Kubernetes Cluster Components.

Nodes

A Node is a worker machine. It can be anything- from a vm to a physical machine- including all sorts of cloud provided vms.

Pods

Pods are a logically grouped collection of containers, meaning one Pod can potentially house a multitude of containers. A Pod gets its own DNS and virtual IP address after it has been created so Kubernetes can load balancer traffic to it. You rarely need to deal with containers directly. Even when debugging, (like looking at logs), you usually invoke kubectl logs deployment/your-app -f instead of looking at a specific container. Although it is possible with -c container_name. The -f does a tail on the log.

Deployments

When creating any kind of resource in Kubernetes, it will use a Deployment in the background. A deployment describes a desired state of the current application. It’s an object you can use to update Pods or a Service to be in a different state, do an update, or rollout new version of your app. You don’t directly control a ReplicaSet, (as described later), but control the deployment object which creates and manages a ReplicaSet.

Services

By default a Pod will get an IP address. However, since Pods are a volatile thing in Kubernetes, you’ll need something more permanent. A queue, mysql, or an internal API, a frontend; these need to be long running and behind a static, unchanging IP or preferably a DNS record.

For this purpose, Kubernetes has Services for which you can define modes of accessibility. Load Balanced, simple IP or internal DNS.

How does Kubernetes know if a service is running correctly? You can configure Health Checks and Availability Checks. A Health Check will check whether a container is running, but that doesn’t mean that your service is running. For that, you have the availability check which pings a different endpoint in your application.

Since Services are pretty important, I recommend that you read up on them later here: Services. Advanced warning though, this document is quite dense. Twenty four A4 pages of networking, services and discovery. It’s also vital to decide whether you want to seriously employ Kubernetes in production.

DNS / Service Discovery

If you create a service in the cluster, that service will get a DNS record in Kubernetes provided by special Kubernetes deployments called kube-proxy and kube-dns. These two provide service discover inside a cluster. If you have a mysql service running and set clusterIP: none, then everyone in the cluster can reach that service by pinging mysql.default.svc.cluster.local. Where:

mysql– is the name of the servicedefault– is the namespace namesvc– is servicescluster.local– is a local cluster domain

The domain can be changed via a custom definition. To access a service outside the cluster, a DNS provider has to be used, and Nginx (for example), to bind an IP address to a record. The public IP address of a service can be queried with the following commands:

- NodePort –

kubectl get -o jsonpath="{.spec.ports[0].nodePort}" services mysql - LoadBalancer –

kubectl get -o jsonpath="{.spec.ports[0].LoadBalancer}" services mysql

Template Files

Like Docker Compose, TerraForm or other service management tools, Kubernetes also provides infrastructure describing templates. What that means is that you rarely need to do anything by hand.

For example, consider the following yaml template which describes an nginx Deployment:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment #(1)

metadata: #(2)

name: nginx-deployment

labels: #(3)

app: nginx

spec: #(4)

replicas: 3 #(5)

selector:

matchLabels:

app: nginx

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: nginx

spec:

containers: #(6)

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.7.9

ports:

- containerPort: 80

This is a simple deployment in which we do the following:

- (1) Define the type of the template with kind

- (2) Add metadata that will identify this deployment and every resource that it would create with a label (3)

- (4) Then comes the spec which describes the desired state

- (5) For the nginx app, have 3 replicas

- (6) This is the template definition for the containers that this Pod will contain

- nginx named container

- nginx:1.7.9 image (docker in this case)

- exposed ports

ReplicaSet

A ReplicaSet is a low level replication manager. It ensures that the correct number of replicates are running for a application. However, Deployments are at a higher level and should always manage ReplicaSets. You rarely need to use ReplicaSets directly unless you have a fringe case in which you want to control the specifics of replication.

DaemonSet

Remember how I said Kubernetes is using Labels all the time? A DaemonSet is a controller that ensures that at daemonized application is always running on a node with a certain label.

For example: you want all the nodes labelled with logger or mission_critical to run an logger / auditing service daemon. Then you create a DaemonSet and give it a node selector called logger or mission_critical. Kubernetes will look for a node that has that label. Always ensure that it will have an instance of that daemon running on it. Thus everyone running on that node will have access to that daemon locally.

In case of my application, the NSQ daemon could be a DaemonSet. Make sure it’s up on a node which has the receiver component running by labelling a node with receiver and specifying a DaemonSet with a receiver application selector.

The DaemonSet has all the benefits of the ReplicaSet. It’s scalable and Kubernetes manages it; which means, all life cycle events are handled by Kube ensuring it never dies, and when it does, it will be immediately replaced.

Scaling

It’s trivial to scale in Kubernetes. The ReplicaSets take care of the number of instances of a Pod to run- as seen in the nginx deployment with the setting replicas:3. It’s up to us to write our application in a way that allows Kubernetes to run multiple copies of it.

Of course the settings are vast. You can specify which replicates must run on what Nodes, or on various waiting times as to how long to wait for an instance to come up. You can read more on this subject here: Horizontal Scaling and here: Interactive Scaling with Kubernetes and of course the details of a ReplicaSet which controls all the scaling made possible in Kubernetes.

Conclusion for Kubernetes

It’s a convenient tool to handle container orchestration. Its unit of work are Pods and it has a layered architecture. The top level layer is Deployments through which you handle all other resources. It’s highly configurable. It provides an API for all calls you make, so potentially, instead of running kubectl you can also write your own logic to send information to the Kubernetes API.

It provides support for all major cloud providers natively by now and it’s completely open source. Feel free to contribute! And check the code if you would like to have a deeper understanding on how it works: Kubernetes on Github.

Minikube

I’m going to use Minikube. Minikube is a local Kubernetes cluster simulator. It’s not great in simulating multiple nodes though, but for starting out and local play without any costs, it’s great. It uses a VM that can be fine tuned if necessary using VirtualBox and the likes.

All of the kube template files that I’ll be using can be found here: Kube files.

NOTE If, later on, you would like to play with scaling but notice that the replicates are always in Pending state, remember that minikube employs a single node only. It might not allow multiple replicas on the same node, or just plainly ran out of resources to use. You can check available resources with the following command:

kubectl get nodes -o yaml

Building the containers

Kubernetes supports most of the containers out there. I’m going to use Docker. For all the services I’ve built, there is a Dockerfile included in the repository. I encourage you to study them. Most of them are simple. For the go services, I’m using a multi stage build that has been recently introduced. The Go services are Alpine Linux based. The Face Recognition service is Python. NSQ and MySQL are using their own containers.

Context

Kubernetes uses namespaces. If you don’t specify any, it will use the default namespace. I’m going to permanently set a context to avoid polluting the default namespace. You do that like this:

❯ kubectl config set-context kube-face-cluster --namespace=face

Context "kube-face-cluster" created.

You have to also start using the context once it’s created, like so:

❯ kubectl config use-context kube-face-cluster

Switched to context "kube-face-cluster".

After this, all kubectl commands will use the namespace face.

Deploying the Application

Overview of Pods and Services:

MySQL

The first Service I’m going to deploy is my database.

I’m using the Kubernetes example located here Kube MySQL which fits my needs. Please note that this file is using a plain password for MYSQL_PASSWORD. I’m going to employ a vault as described here Kubernetes Secrets.

I’ve created a secret locally as described in that document using a secret yaml:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: kube-face-secret

type: Opaque

data:

mysql_password: base64codehere

I created the base64 code via the following command:

echo -n "ubersecurepassword" | base64

And, this is what you’ll see in my deployment yaml file:

...

- name: MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: kube-face-secret

key: mysql_password

...

Another thing worth mentioning: It’s using a volume to persist the database. The volume definition is as follows:

...

volumeMounts:

- name: mysql-persistent-storage

mountPath: /var/lib/mysql

...

volumes:

- name: mysql-persistent-storage

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: mysql-pv-claim

...

presistentVolumeClain is key here. This tells Kubernetes that this resource requires a persistent volume. How it’s provided is abstracted away from the user. You can be sure that Kubernetes will provide a volume that will always be there. It is similar to Pods. To read up on the details, check out this document: Kubernetes Persistent Volumes.

Deploying the mysql Service is done with the following command:

kubectl apply -f mysql.yaml

apply vs create. In short, apply is considered a declarative object configuration command while create is imperative. What this means for now is that ‘create’ is usually for a one of tasks, like running something or creating a deployment. While, when using apply, the user doesn’t define the action to be taken. That will be defined by Kubernetes based on the current status of the cluster. Thus, when there is no service called mysql and I’m calling apply -f mysql.yaml it will create the service. When running again, Kubernetes won’t do anything. But if I would run create again it will throw an error saying the service is already created.

For more information, check out the following docs: Kubernetes Object Management, Imperative Configuration, Declarative Configuration.

To see progress information, run:

# Describes the whole process

kubectl describe deployment mysql

# Shows only the pod

kubectl get pods -l app=mysql

Output should be similar to this:

...

Type Status Reason

---- ------ ------

Available True MinimumReplicasAvailable

Progressing True NewReplicaSetAvailable

OldReplicaSets: <none>

NewReplicaSet: mysql-55cd6b9f47 (1/1 replicas created)

...

Or in case of get pods:

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

mysql-78dbbd9c49-k6sdv 1/1 Running 0 18s

To test the instance, run the following snippet:

kubectl run -it --rm --image=mysql:5.6 --restart=Never mysql-client -- mysql -h mysql -pyourpasswordhere

GOTCHA: If you change the password now, it’s not enough to re-apply your yaml file to update the container. Since the DB is persisted, the password will not be changed. You have to delete the whole deployment with kubectl delete -f mysql.yaml.

You should see the following when running a show databases.

If you don't see a command prompt, try pressing enter.

mysql>

mysql>

mysql> show databases;

+--------------------+

| Database |

+--------------------+

| information_schema |

| kube |

| mysql |

| performance_schema |

+--------------------+

4 rows in set (0.00 sec)

mysql> exit

Bye

You’ll also notice that I’ve mounted a file located here: Database Setup SQL into the container. MySQL container automatically executes these. That file will bootstrap some data and the schema I’m going to use.

The volume definition is as follows:

volumeMounts:

- name: mysql-persistent-storage

mountPath: /var/lib/mysql

- name: bootstrap-script

mountPath: /docker-entrypoint-initdb.d/database_setup.sql

volumes:

- name: mysql-persistent-storage

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: mysql-pv-claim

- name: bootstrap-script

hostPath:

path: /Users/hannibal/golang/src/github.com/Skarlso/kube-cluster-sample/database_setup.sql

type: File

To check if the bootstrap script was successful, run this:

~/golang/src/github.com/Skarlso/kube-cluster-sample/kube_files master*

❯ kubectl run -it --rm --image=mysql:5.6 --restart=Never mysql-client -- mysql -h mysql -uroot -pyourpasswordhere kube

If you don't see a command prompt, try pressing enter.

mysql> show tables;

+----------------+

| Tables_in_kube |

+----------------+

| images |

| person |

| person_images |

+----------------+

3 rows in set (0.00 sec)

mysql>

This concludes the database service setup. Logs for this service can be viewed with the following command:

kubectl logs deployment/mysql -f

NSQ Lookup

The NSQ Lookup will run as an internal service. It doesn’t need access from the outside, so I’m setting clusterIP: None which will tell Kubernetes that this service is a headless service. This means that it won’t be load balanced, and it won’t be a single IP service. The DNS will be based upon service selectors.

Our NSQ Lookup selector is:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: nsqlookup

Thus, the internal DNS will look like this: nsqlookup.default.svc.cluster.local.

Headless services are described in detail here: Headless Service.

Basically it’s the same as MySQL, just with slight modifications. As stated earlier, I’m using NSQ’s own Docker Image called nsqio/nsq. All nsq commands are there, so nsqd will also use this image just with a different command. For nsqlookupd, the command is:

command: ["/nsqlookupd"]

args: ["--broadcast-address=nsqlookup.default.svc.cluster.local"]

What’s the --broadcast-address for, you might ask? By default, nsqlookup will use the hostname as broadcast address. When the consumer runs a callback it will try to connect to something like: http://nsqlookup-234kf-asdf:4161/lookup?topics=image. Please note that nsqlookup-234kf-asdf is the hostname of the container. By setting the broadcast-address to the internal DNS, the callback will be: http://nsqlookup.default.svc.cluster.local:4161/lookup?topic=images. Which will work as expected.

NSQ Lookup also requires two ports forwarded: One for broadcasting and one for nsqd callback. These are exposed in the Dockerfile, and then utilized in the Kubernetes template. Like this:

In the container template:

ports:

- containerPort: 4160

hostPort: 4160

- containerPort: 4161

hostPort: 4161

In the service template:

spec:

ports:

- name: tcp

protocol: TCP

port: 4160

targetPort: 4160

- name: http

protocol: TCP

port: 4161

targetPort: 4161

Names are required by Kubernetes.

To create this service, I’m using the same command as before:

kubectl apply -f nsqlookup.yaml

This concludes nsqlookupd. Two of the major players are in the sack!

Receiver

This is a more complex one. The receiver will do three things:

- Create some deployments;

- Create the nsq daemon;

- Expose the service to the public.

Deployments

The first deployment it creates is its own. The receiver’s container is skarlso/kube-receiver-alpine.

Nsq Daemon

The receiver starts an nsq daemon. As stated earlier, the receiver runs an nsqd with it-self. It does this so talking to it can happen locally and not over the network. By making the receiver do this, they will end up on the same node.

NSQ daemon also needs some adjustments and parameters.

ports:

- containerPort: 4150

hostPort: 4150

- containerPort: 4151

hostPort: 4151

env:

- name: NSQLOOKUP_ADDRESS

value: nsqlookup.default.svc.cluster.local

- name: NSQ_BROADCAST_ADDRESS

value: nsqd.default.svc.cluster.local

command: ["/nsqd"]

args: ["--lookupd-tcp-address=$(NSQLOOKUP_ADDRESS):4160", "--broadcast-address=$(NSQ_BROADCAST_ADDRESS)"]

You can see that the lookup-tcp-address and the broadcast-address are set. Lookup tcp address is the DNS for the nsqlookupd service. And the broadcast address is necessary, just like with nsqlookupd, so the callbacks are working properly.

Public facing

Now, this is the first time I’m deploying a public facing service. There are two options. I could use a LoadBalancer since this API will be under heavy load. And if this would be deployed anywhere in production, then it should be using one.

I’m doing this locally though- with one node- so something called a NodePort is enough. A NodePort exposes a service on each node’s IP at a static port. If not specified, it will assign a random port on the host between 30000-32767. But it can also be configured to be a specific port, using nodePort in the template file. To reach this service, use <NodeIP>:<NodePort>. If more than one node is configured, a LoadBalancer can multiplex them to a single IP.

For further information, check out this document: Publishing Services.

Putting this all together, we’ll get a receiver-service for which the template for is as follows:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: receiver-service

spec:

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 8000

targetPort: 8000

selector:

app: receiver

type: NodePort

For a fixed nodePort on 8000 a definition of nodePort must be provided:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: receiver-service

spec:

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 8000

targetPort: 8000

selector:

app: receiver

type: NodePort

nodePort: 8000

Image processor

The Image Processor is where I’m handling passing off images to be identified. It should have access to nsqlookupd, mysql and the gRPC endpoint of the face recognition service. This is actually quite a boring service. In fact, it’s not even a service at all. It doesn’t expose anything, and thus it’s the first deployment only component. For brevity, here is the whole template:

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: image-processor-deployment

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: image-processor

replicas: 1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: image-processor

spec:

containers:

- name: image-processor

image: skarlso/kube-processor-alpine:latest

env:

- name: MYSQL_CONNECTION

value: "mysql.default.svc.cluster.local"

- name: MYSQL_USERPASSWORD

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: kube-face-secret

key: mysql_userpassword

- name: MYSQL_PORT

# TIL: If this is 3306 without " kubectl throws an error.

value: "3306"

- name: MYSQL_DBNAME

value: kube

- name: NSQ_LOOKUP_ADDRESS

value: "nsqlookup.default.svc.cluster.local:4161"

- name: GRPC_ADDRESS

value: "face-recog.default.svc.cluster.local:50051"

The only interesting points in this file are the multitude of environment properties that are used to configure the application. Note the nsqlookupd address and the grpc address.

To create this deployment, run:

kubectl apply -f image_processor.yaml

Face - Recognition

The face recognition service does have a service. It’s a simple one. Only needed by image-processor. It’s template is as follows:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: face-recog

spec:

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 50051

targetPort: 50051

selector:

app: face-recog

clusterIP: None

The more interesting part is that it requires two volumes. The two volumes are known_people and unknown_people. Can you guess what they will contain? Yep, images. The known_people volume contains all the images associated to the known people in the database. The unknown_people volume will contain all new images. And that’s the path we will need to use when sending images from the receiver; that is wherever the mount point points too, which in my case is /unknown_people. Basically, the path needs to be one that the face recognition service can access.

Now, with Kubernetes and Docker, this is easy. It can be a mounted S3 or some kind of nfs or a local mount from host to guest. The possibilities are endless (around a dozen or so). I’m going to use a local mount for the sake of simplicity.

Mounting a volume is done in two parts. Firstly, the Dockerfile has to specify volumes:

VOLUME [ "/unknown_people", "/known_people" ]

Secondly, the Kubernetes template needs add volumeMounts as seen in the MySQL service; the difference being hostPath instead of claimed volume:

volumeMounts:

- name: known-people-storage

mountPath: /known_people

- name: unknown-people-storage

mountPath: /unknown_people

volumes:

- name: known-people-storage

hostPath:

path: /Users/hannibal/Temp/known_people

type: Directory

- name: unknown-people-storage

hostPath:

path: /Users/hannibal/Temp/

type: Directory

We also need to set the known_people folder config setting for the face recognition service. This is done via an environment property:

env:

- name: KNOWN_PEOPLE

value: "/known_people"

Then the Python code will look up images, like this:

known_people = os.getenv('KNOWN_PEOPLE', 'known_people')

print("Known people images location is: %s" % known_people)

images = self.image_files_in_folder(known_people)

Where image_files_in_folder is:

def image_files_in_folder(self, folder):

return [os.path.join(folder, f) for f in os.listdir(folder) if re.match(r'.*\.(jpg|jpeg|png)', f, flags=re.I)]

Neat.

Now, if the receiver receives a request (and sends it off further down the line) similar to the one below…

curl -d '{"path":"/unknown_people/unknown220.jpg"}' http://192.168.99.100:30251/image/post

…it will look for an image called unknown220.jpg under /unknown_people, locate an image in the known_folder that corresponds to the person in the unknown image and return the name of the image that matches.

Looking at logs, you should see something like this:

# Receiver

❯ curl -d '{"path":"/unknown_people/unknown219.jpg"}' http://192.168.99.100:30251/image/post

got path: {Path:/unknown_people/unknown219.jpg}

image saved with id: 4

image sent to nsq

# Image Processor

2018/03/26 18:11:21 INF 1 [images/ch] querying nsqlookupd http://nsqlookup.default.svc.cluster.local:4161/lookup?topic=images

2018/03/26 18:11:59 Got a message: 4

2018/03/26 18:11:59 Processing image id: 4

2018/03/26 18:12:00 got person: Hannibal

2018/03/26 18:12:00 updating record with person id

2018/03/26 18:12:00 done

And that concludes all of the services that we need to deploy.

Frontend

Lastly, there is a small web-app which displays the information in the db for convenience. This is also a public facing service with the same parameters as the receiver.

It looks like this:

Recap

We are now at the point in which I’ve deployed a bunch of services. A recap off the commands I’ve used so far:

kubectl apply -f mysql.yaml

kubectl apply -f nsqlookup.yaml

kubectl apply -f receiver.yaml

kubectl apply -f image_processor.yaml

kubectl apply -f face_recognition.yaml

kubectl apply -f frontend.yaml

These could be in any order since the application does not allocate connections on start. (Except for image_processor’s NSQ consumer. But that re-tries.)

Query-ing kube for running pods with kubectl get pods should show something like this if there were no errors:

❯ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

face-recog-6bf449c6f-qg5tr 1/1 Running 0 1m

image-processor-deployment-6467468c9d-cvx6m 1/1 Running 0 31s

mysql-7d667c75f4-bwghw 1/1 Running 0 36s

nsqd-584954c44c-299dz 1/1 Running 0 26s

nsqlookup-7f5bdfcb87-jkdl7 1/1 Running 0 11s

receiver-deployment-5cb4797598-sf5ds 1/1 Running 0 26s

Running minikube service list:

❯ minikube service list

|-------------|----------------------|-----------------------------|

| NAMESPACE | NAME | URL |

|-------------|----------------------|-----------------------------|

| default | face-recog | No node port |

| default | kubernetes | No node port |

| default | mysql | No node port |

| default | nsqd | No node port |

| default | nsqlookup | No node port |

| default | receiver-service | http://192.168.99.100:30251 |

| kube-system | kube-dns | No node port |

| kube-system | kubernetes-dashboard | http://192.168.99.100:30000 |

|-------------|----------------------|-----------------------------|

Rolling update

What happens during a rolling update?

As it happens during software development, change is requested/needed to some parts of the system. So what happens to our cluster if I change one of its components without breaking the others whilst also maintaining backwards compatibility with no disruption to user experience? Thankfully Kubernetes can help with that.

What I don’t like is that the API only handles one image at a time. Unfortunately there is no bulk upload option.

Code

Currently, we have the following code segment dealing with a single image:

// PostImage handles a post of an image. Saves it to the database

// and sends it to NSQ for further processing.

func PostImage(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

...

}

func main() {

router := mux.NewRouter()

router.HandleFunc("/image/post", PostImage).Methods("POST")

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":8000", router))

}

We have two options: Add a new endpoint with /images/post and make the client use that, or modify the existing one.

The new client code has the advantage in that it can fall back to submitting the old way if the new endpoint isn’t available. The old client code, however, doesn’t have this advantage so we can’t change the way our code works right now. Consider this: You have 90 servers and you do a slow paced rolling update that will take out servers one step at a time whilst doing an update. If an update lasts around a minute, the whole process will take around one and a half hours to complete, (not counting any parallel updates).

During this time, some of your servers will run the new code and some will run the old one. Calls are load balanced, thus you have no control over which servers will be hit. If a client is trying to do a call the new way but hits an old server, the client will fail. The client can try and fallback, but since you eliminated the old version it will not succeed unless it, by mere chance, hits a server with the new code (assuming no sticky sessions are set).

Also, once all your servers are updated, an old client will not be able to use your service any longer.

Now, you can argue that you don’t want to keep old versions of your code forever. And that’s true in a sense. That’s why we are going to modify the old code to simply call the new one with some slight augmentations. This way, once all clients have been migrated, the code can simply be deleted without any problems.

New Endpoint

Let’s add a new route method:

...

router.HandleFunc("/images/post", PostImages).Methods("POST")

...

Updating the old one to call the new one with a modified body looks like this:

// PostImage handles a post of an image. Saves it to the database

// and sends it to NSQ for further processing.

func PostImage(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var p Path

err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&p)

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "got error while decoding body: %s", err)

return

}

fmt.Fprintf(w, "got path: %+v\n", p)

var ps Paths

paths := make([]Path, 0)

paths = append(paths, p)

ps.Paths = paths

var pathsJSON bytes.Buffer

err = json.NewEncoder(&pathsJSON).Encode(ps)

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "failed to encode paths: %s", err)

return

}

r.Body = ioutil.NopCloser(&pathsJSON)

r.ContentLength = int64(pathsJSON.Len())

PostImages(w, r)

}

Well, the naming could be better, but you should get the basic idea. I’m modifying the incoming single path by wrapping it into the new format and sending it over to the new endpoint handler. And that’s it! There are a few more modifications. To check them out, take a look at this PR: Rolling Update Bulk Image Path PR.

Now, the receiver can be called in two ways:

# Single Path:

curl -d '{"path":"unknown4456.jpg"}' http://127.0.0.1:8000/image/post

# Multiple Paths:

curl -d '{"paths":[{"path":"unknown4456.jpg"}]}' http://127.0.0.1:8000/images/post

Here, the client is curl. Normally, if the client is a service, I would modify it that in case the new end-point throws a 404 it would try the old one next.

For brevity, I’m not modifying NSQ and the others to handle bulk image processing; they will still receive it one by one. I’ll leave that up to you as homework ;)

New Image

To perform a rolling update, I must create a new image first from the receiver service.

docker build -t skarlso/kube-receiver-alpine:v1.1 .

Once this is complete, we can begin rolling out the change.

Rolling update

In Kubernetes, you can configure your rolling update in multiple ways:

Manual Update

If I was using a container version in my config file called v1.0, then doing an update is simply calling:

kubectl rolling-update receiver --image:skarlso/kube-receiver-alpine:v1.1

If there is a problem during the rollout we can always rollback.

kubectl rolling-update receiver --rollback

It will set back the previous version. No fuss, no muss.

Apply a new configuration file

The problem with by-hand updates is that they aren’t in source control.

Consider this: Something has changed, A couple of servers got updated by hand to do a quick “patch fix”, but nobody witnessed it and it wasn’t documented. A new person comes along and does a change to the template and applies the template to the cluster. All the servers are updated, and then all of a sudden there is a service outage.

Long story short, the servers which got updated are written over because the template doesn’t reflect what has been done manually.

The recommended way is to change the template in order to use the new version, and than apply the template with the apply command.

Kubernetes recommends that a Deployment with ReplicaSets should handle a rollout. This means there must be at least two replicates present for a rolling update. If less than two replicates are present then the update won’t work (unless maxUnavailable is set to 1). I increase the replica count in yaml. I also set the new image version for the receiver container.

replicas: 2

...

spec:

containers:

- name: receiver

image: skarlso/kube-receiver-alpine:v1.1

...

Looking at the progress, this is what you should see :

❯ kubectl rollout status deployment/receiver-deployment

Waiting for rollout to finish: 1 out of 2 new replicas have been updated...

You can add in additional rollout configuration settings by specifying the strategy part of the template like this:

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate

rollingUpdate:

maxSurge: 1

maxUnavailable: 0

Additional information on rolling update can be found in the below documents: Deployment Rolling Update, Updating a Deployment, Manage Deployments, Rolling Update using ReplicaController.

NOTE MINIKUBE USERS: Since we are doing this on a local machine with one node and 1 replica of an application, we have to set maxUnavailable to 1; otherwise Kubernetes won’t allow the update to happen, and the new version will remain in Pending state. That’s because we aren’t allowing for a services to exist with no running containers; which basically means service outage.

Scaling

Scaling is dead easy with Kubernetes. Since it’s managing the whole cluster, you basically just need to put a number into the template of the desired replicas to use.

This has been a great post so far, but it’s getting too long. I’m planning on writing a follow-up where I will be truly scaling things up on AWS with multiple nodes and replicas; plus deploying a Kubernetes cluster with Kops. So stay tuned!

Cleanup

kubectl delete deployments --all

kubectl delete services -all

Final Words

And that’s it ladies and gentlemen. We wrote, deployed, updated and scaled (well, not yet really) a distributed application with Kubernetes.

If you have any questions, please feel free to chat in the comments below. I’m happy to answer.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this. I know it’s quite long; I was thinking of splitting it up multiple posts, but having a cohesive, one page guide is useful and makes it easy to find, save, and print.

Thank you for reading, Gergely.