Hello Everybody.

Today I’d like to write a little bit about a python course I did.

It’s an 8 week course on algorithmic programming with fun little projects. I’d like to write down some of my solutions with pseudo code for my own better understanding and for the sake of sharing knowledge. I won’t, however, share full projects since that would be against the honour code.

Let’s begin.

Week Zero

This week was all about getting the hang out of reading the posts and the documentation and the questions and getting used to the wordings. The tutors really out did themselves. They tried to make a course that can be both funny and teach something at the same time which is anything but easy.

Even though the tasks that were given were interesting al-bight at times a little bit far stretched and could have been easier done if used something else to complete them. But if we would have done that, what’s the point of it all then?

So I’ll try to recall everything solely based on my notes taken in those 8 weeks. Let’s see how much I truly learned.

Assignment of week one

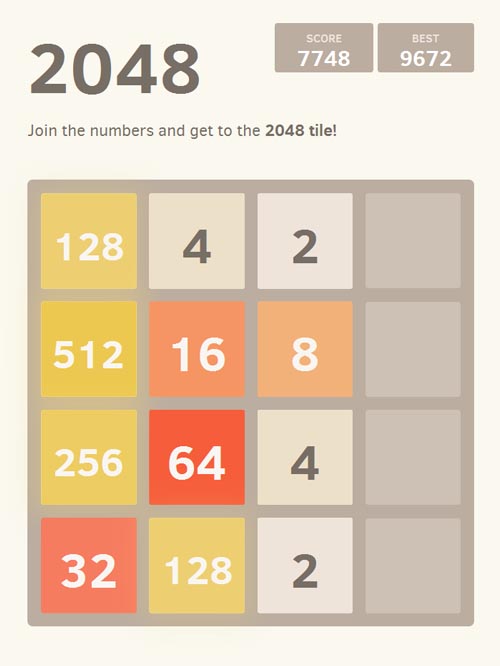

We were to build the game 2048 which if you played you know what it is all about.

The goal is to add up numbers so that higher and higher numbers are created. There is no real “end” of the game. You can continue as long as you have space left although the intended goal is to create 2048. There are a couple of clones of this game and we were supposed to write one this time of our own.

We approached this game with the intention of refreshing our memory about Python. Handling matrices python syntax, counting indices and a bit of assessment about the general understanding of Mathematics and programming from the populace.

I must say it was hard. It was hard to get back into the habit of properly thinking about something at first. It was hard to get used to Math again which I missed for a very long time. I forgot many things and as English is not my first language many things written about Math in English were extremely hard to understand in the beginning.

But thankfully for my trusty mathematics Bible in Hungarian I was saved.

This book is 1448 pages long but contained all the information necessary to get my mind back into the game. And oh boy was it worth the initial trouble. I had to first realize that I forgot so much it was very painful and immensely disappointing, frustrating and shameful. But you should never give up and so I fought my way through it.

And it was extremely helpful to do Tests First. As the grading was based on how many of a given set of Unit Tests were passing it was very helpful to start tests first which were leading the design of the program. Also it was crucial to work in as little chunks as possible since one could easily lost himself trying to grasp a problem proving to be too large to look at from afar.

The hard part about this project was the Merging of the numbers and creating the proper grid which results from the Merge. Here are some examples:

[2, 0, 2, 4]should return[4, 4, 0, 0][0, 0, 2, 2]should return[4, 0, 0, 0][2, 2, 0, 0]should return[4, 0, 0, 0][2, 2, 2, 2]should return[4, 4, 0, 0][8, 16, 16, 8]should return[8, 32, 8, 0]

In order to achieve this you must trim the zeros like this [2,2,4] and than produce the result which is [4,4] and put a couple of zeros at the end [4,4,0,0]. My first though was to use the Deque class in Python in order to achieve this but that was an outside module which was not allowed.

It was an interesting way to begin the course. Many people left at this point and were leaving afterwards too. Most of them in frustration that they were missing the python knowledge the rest out of frustration of not knowing the necessary math. At the end though it was getting easier to follow the problems after we got used to the conventions and sentence structures. The professors were also helpful and sometimes re-worded some of the descriptions to better describe what they wanted.

Week One

So after a hard start we moved on to a very interesting week one. This one got me into a certain game I don’t want to see ever again. It’s name: Cookie Clicker.

We sort of had to re-create the cookie clicker but without the clicking. We only were supposed to re-create the buying of upgrades and simulate a sequence of clicks via the means of a cycle.

In this week the description of the tasks was, at the least, confusing. They started to use the term _time _which lead many to believe that we were somehow supposed to use python’s date / time methods and libraries. But after a couple of re-reads it was apparent that by _time _they actually were referring to cycle count.** **

Knowing this made the task at hand a lot easier. This time around our main focus were the following:

- Mathematical Sums

- Finding the Max

- Higher - Order functions

- Plotting with Python

The course just went into overdrive. We were looking lot at things like these:

∑n i=0 α^i = α^0 + α^1 + α^2 + ... + α^n = α^(n+1) − 1 / α − 1

(2021 Hindsight): It’s funny how I’m looking at this now, and it immeditely makes perfect sense. I love how evolved in that regard over the time.

It was rather awesome though frustrating at first like I wrote earlier. These were the easier one.

Finding the maximum is trivial. Especially if you are using a built in **max **provided by Python. But if you mix it with Higher-Order functions it gets interesting. If you want to do anything else as well and not just a max, for example getting the index of the maximum item as well, you usually end up writing a custom Max any ways.

Plotting in Python was exquisite interesting. The garphs which were produced showed as an insight into how powerful a solution really is or how effective. Here came in the Big-O notations almost. To see if a function was exponential, logarithmic or plain polynomial. O(n), O(n^2), O(logn) etc, etc.

This resulted in very interesting graphs like this:

Week Two

So last week we had plotting and counting this week was even more interesting. Week Two’s main focus was Probability. Specifically the Monte Carlo methods. Tl;dr; it describes that if you try something enough times you can derive a result that will be, with very high probability, the one you are looking for (expected value).

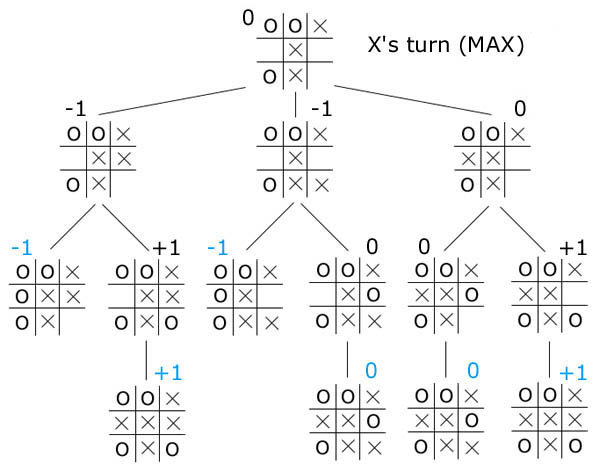

We tried out this algorithm by playing a nice game of tic-tac-toe.

The point of this exercise was to create a machine player which, after running a 1000 or so random scenarios, was choosing the best option given a certain game state. It was difficult to get the results to always return a correct answer. At this point last weeks plotting became important since if your Monet Carlo algorithm was not fast enough the program was running increasingly slower and slower.

I was not very satisfied with my solution. It worked, but it was very slow and it wasn’t always returning the best option.

Week Three

So what comes after probability? Correct. **Combinatorics. **

The next hill to climb was combinatorics. Fortunately for me I love probability and combinatorics so this was a little bit easier for me. I was getting the hang out of function calculation as well so I wrote better homework and better projects at this point. Which is the aim of the course, right?

The game we used for this approach was Yahtzee.

Now let me say this without too much remorse. I truly, fully and with all my heart, hate Yahtzee. I think it’s stupid. I’m sorry. I truly do. The only thing I can think of when I hear yahtzee is the South Park version of it.

South Park Version of Yahtzee + Tron:

I share the enthusiastic look of Stan here.

Anyhow, moving on. Thank to the coursera Gods we weren’t suppose to write a whole game of Yathzee just a very simplified version of it. We were supposed to count the upper combinations on the second throw. So you already have one throw and you must choose how many die you want to hold on to to maximise the possibility of the best outcome possible. Huh. come again?

So you already had a hand. And now the program was to determine which die you were supposed to hold on too in order to maximise the score you can achieve with the remaining two throws.

There were a few interesting things that came in with this task. For example this was the first time I could use a Dict init from a list with a zip.

hand_dict = dict(zip(list(hand), []*len(hand)))

And this was the point in course were I found perhaps the most interesting thing. I found an actual use for reduce which was working. I was beginning to get into the habit of using map, filter, reduce.

This was the beauty:

my_list = reduce(lambda z, x: z + [y + [x] for y in z], hand, [[]])

This piece of code produced all the combinations of a given hand which was a list of Tuples. It merged them into a list of lists which I created a list of Tuples out from. After this my life was never ever the same again.

Week Four

For me this was the most interesting part of the course. I LOVED this task. Focus was:

- Python Generators

- Stacks / Queues

- Inheritance in Python

- Girds

- Grid Search / Breadth First Search

And the task with which we were supposed to achieve this was..

Zombie Apocalypse. It was sort of like Conway’s Game of Life. Given a grid in which there were Zombies, Humans and Obstacles.

The Zombies could only move up, down, left, right. The humans could flee diagonally and none of them could penetrate an obstacle. It was very much fun to write this. The most challenge was to learn the proper implementation of the breadth first search algorithm as the Zombies had to detect the nearest Humans to move towards to and the Humans needed to see the nearest Zombies to flee from.

Week Five

Halfway through it was become difficult to maintain the time needed for this course. I was finding myself applying a few late days here and there. This was a two months course after all. I did not have all the time in the world at my disposal. But I managed to submit everything without penalties.

So this weeks task was rather mundane. It was a world wrangler. Which means given a word generate valid words from the letters in the provided word.

The algorithm we were supposed to use though was for me a bit of a challenge. I’ll be honest with you, for me, it was a little bit hard to wrap my head around this one. But eventually I succeeded.

It was Merge-Sort and Recursion. Let me tell you this now, I hate merge-sort. Recursion I do love though. What I never learned though and was very interesting for me to learn now was recurrences in mathematics. Well never learned is a bit harsh since I knew Fibonacci already and Pascal’s Triangle but the mathematical definition was a refreshing new view. I’m talking about Recurrence Relations.

F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2)

This is the Recurrence relation of the famous Fibonacci. Easy, right? Well the hard part is when you are trying to get the closed-form-expression of a Recurrence.

Week Six

Finally it was coming to an end. The last week was easy so this week had to have a punch. And oh boy it did. This weeks focus:

- Trees

- Lambdas

- Illustration of Trees

- Minimax

- Depth First Search

If I hated merge-sort I hated minimax more. I don’t know why but it was again very hard for me to properly grasp this concept. I mean I understood what needed to be done of course but writing it done with code proved to be more difficult then I thought it would be.

After hours of research and reading finally I could come up with a solution which was working. I wouldn’t say it was good. But it was working.

The game with which we were supposed to demonstrate this algorithm was. Tic-Tac-Toe. Turns out that it’s rather common place to show off minimax with tic-tac-toe as it was fewer possibilities. The point of the exercise was the following.:

To create trees out of the possible moves given a certain game state. This time we wanted to make absolutely sure that if we can’t win the game at least we won’t loose it. And that’s the point of minimax. It will minimize your losses.

Now there are several things about this algorithm that are hard.

Performance of Minimax

It has and always will be a very interesting task for programmers to try to achieve a better performance for these calculations. Since it’s trying to build up a tree with all the possible combinations a game can have it will end up with a huge tree which will take ages to traverse.

A few of the solutions could be to exit the search once you have a definitive answer. If you find a winning move there is no point of looking any further. You just stop.

You can create the tree dynamically. You can make it somehow intelligent enough to predict a possible best first move and then use minimax on the rest. Or use Alpha-beta pruning.

Week Seven

And so we are coming to an end. Last weeks assignment was basically to put all the previous weeks knowledge together to create the application called 15 puzzle.

Now, there was however a little addition to the previous knowledge. It was invariants. Now, I love Logic. And I’ve been actually using invariants in computer science programming and testing for a long time so this part was not really a problem.

An example of an invariant in python would be something like this:

while x <= 5:

x = x + 1

This is a loop invariant example. In you find a very useful invariant in your program you can write an assert for it which will help you debug your code and work in small chunks. Invariants will make refactoring your code a hell of a lot easier. As if your invariant is suddenly false you need to check what went wrong.

while x <= 5:

x = x + 1

assert x <= 6

This assert will make sure that if your invariant for whatever reason isn’t true your code fails immediately.

End Credits

So this was the end of the course. I learned a a lot from this course and I’m very proud of myself for completing it. I took away a lot from this course. I took away confidence and logical thinking. I took away greater trust in my Python knowledge and that it’s very important to keep my skills from deteriorating.

And I think math is important for proper, deep understanding of programming as a science. I think refreshing my math skills gave me at least a deeper trust in my ability to write a piece of code however complicated it might appear. After writing a minimax algorithm I think some Hibernate with DIP and SRP will prove to be less of a problem. Or at least a different category of a problem.. Hehe.

Thanks for reading! Gergely.